The evocative music of award-winning composer, JONATHAN DAVID LITTLE, is notable for its mystical beauty, intensity, richness and intricacy. ...

WORLDWIDE CRITICAL OPINION:

- [of "Polyhymnia":] “Gorgeous, exciting, chilling and surprising … an elegant gift to the ears. There are no words to describe this work … superlative … spine-tingling … There is just no classification for this work … the complexity, the beauty, the elegance, the intensity … so otherworldly … indescribable” – Reviews New Age [5/5 stars] (February, 2012) (Spain)

- “a heart-rending panorama: it is immensely poetic, almost otherwordly, and employs an exceptionally hypnotic array of musical colour” – John Wheatley, in Tempo (Cambridge University Press, January 2012) (UK)

- “very well crafted ... very effective” – Stephen Layton, Choral Conductor and Director of Music, Trinity College, Cambridge (October 2009) (UK)

- “Here, Little demonstrates his command of orchestration ... lush and at ease with the tropes of modernist tonal music … the crafting of orchestration is finely honed” – Helen O’Brien, Music Forum (May-July 2009) (Australia)

- “An inspired creation ... beautifully expansive ... voluptuous sonorities” – Patric Standford, Music & Vision (May 2009) (UK)

- “mightily impressed” – Martin Anderson, Founder and Managing Director, Toccata Classics (January, 2009) (UK)

- “a major new, original and quite brilliant classical voice” – Lynn René Bayley, citation in “The Want List 2008”, Fanfare Magazine (Nov-Dec 2008, USA)

*** A FANFARE MAGAZINE RECOMMENDED RECORDING FOR 2008 ***

- “This is music that brings to mind so much else but at the same time isn't quite like anything you've heard before. … [a] whirling kaleidoscope of sounds. … An extraordinary range of sensations. ... This is certainly novel stuff and I suspect time will prove it to be a good deal more than that.” – Simon Thomas, Music OMH (November 2008) (UK)

- “Little’s music sounds like no one else’s. Not anyone’s. ... to put it into words degrades the astonishing range of colors and moods he creates. … Trust me, once you’re about halfway through the title work, you won’t be able to take it off. … Mr. Little is quite a talent indeed.” – Lynn René Bayley, in Fanfare (May-June 2008) (USA)

- “innovative music … incandescent … a positively dynamic musical palette … moving the listener irrevocably onward to a brightly illuminated plain of poetic splendour, rhythm and ecstasy” – John Wheatley, in Tempo (Cambridge University Press, January 2008) (UK)

- “immense creativity and innovation while remaining accessible to new listeners” – ASCAP Playback Magazine (Summer, 2006) (New York, USA)

- “innovative and accessible to both musicians and audiences” – Keith Lowde, former Deputy Managing Director and Company Secretary, Music-Copyright Protection Society [MCPS] (2006) (London, UK)

- “touching music … a unique voice” – Maestro Robert Ian Winstin, Executive Director of the Foundation for New Music (2006) (Virginia, USA)

Artists who have performed or recorded the works of Jonathan Little include: Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Kiev Philharmonic Orchestra; Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra; Soloists of the Sofia Opera; mezzo-soprano Veronica McHale (Chicago); Vox Moderne; Bath Camerata; Tallis Chamber Choir.

Jonathan Little's Performing Rights are assigned to ASCAP (for clearance see: www.ascap.com – “ACE Title Search” – “Search the Database” – Writers / Find “Jonathan Little”)

Press

NAVONA RECORDS update ARTIST PAGE for JONATHAN DAVID LITTLE

(external link)

Includes updated Bio and details of Recorded Music by Jonathan David Little released on the Navona Records label (USA) [featuring "Polyhymnia" and "Woefully Arrayed"].

Now available on PODCAST: Composer interview with Jonathan David Little on POLYCHORALISM

(external link)

Now available on PODCAST: Composer interview with Jonathan David Little (on creating and recording contemporary "polychoral music"?).

Interview on WCPE, The Classical Station (North Carolina)

(external link)

If you missed the interview with composer Jonathan David Little on Preview yesterday evening, you can hear it anytime here [LINK ABOVE]. In the interview, Rob Kennedy and Jonathan talked about his compositions in the 17th-century polychoral style. You can hear several of these works on his CD Woefully Arrayed.

https://theclassicalstation.org

[CONVERSATIONS WITH COMPOSERS]

https://theclassicalstation.org/listen/conversations-2/conversations-with-composers/

World première performance of "CRUCIFIXUS"

(external link)

World première performance of Crucifixus by Jonathan David Little, an anthem for Triple Choir (in 12 parts) with organ accompaniment.

Performed by the massed voices of the Chichester Singers, also joined by the Grand Choeur du Conservatoire de Chartres, the Southern Pro Musica Brass, and Richard Barnes (organ), directed by Jonathan Willcocks (in his 40th anniversary concert as Music Director of the 120-strong Chichester Singers).

Given 22 June 2019 - in Chichester Cathedral, to commemorate the 60th Anniversary of the twinning of Chartres (France) with Chichester (England).

https://musicinportsmouth.co.uk/noticeboard/music-to-celebrate-60-years-of-twinning-of-chartres-with-chichester/

AUSTRALIA PRIZE for Distinctive Work 2018 - FINALIST

(external link)

2018 CHASS AUSTRALIA PRIZES Shortlists Announced: The [Australian National] Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (CHASS) has announced the shortlists for its prestigious 2018 Australia Prizes, which will be presented on 29th October in Melbourne, and are Australia's leading prizes in the Arts and Humanities.

Professor Jonathan David Little is nominated for his "International Polychoral Music Research, Creation and Recording Project", in the "Distinctive Work" category (one of four Australia Prize categories).

Sponsored by Routledge, the "Distinctive Work" Prize is for an exceptional artistic performance, exhibition, film, television show, play, composition or practical contribution to arts policy.

This same two-year polychoral music project (2015-17), part-sponsored by the Australia Council, has already seen its subsequent CD release, "Woefully Arrayed" (on Navona NV6113, USA), receive the highest international plaudits.

"Woefully Arrayed" - which features three leading choirs from the US and USA - was nominated in America for "Best Classical Music Recording" at the inaugural RoundGlass Global Music Awards 2018 (26th January, Edison Ballroom, New York), while its "Kyrie" was British winner of a BBC Radio 3 / Royal Philharmonic Society "Encore Choral" Award.

This was the first new, large-scale polychoral music research, creation and recording project of modern times. Works produced involve intricate, multi-part, multi-divisi and unusual spatial "split choir" effects – reimagining ancient techniques in contemporary contexts, all captured via cutting-edge recording technology, and promulgated worldwide. Ancient techniques were re-invented, derived from those once so brilliantly employed to create extra depth for choral performance in large spaces in the 16th and 17th centuries, so realising "surround-sound"-like effects. In order to aid performers and listeners, diagrams showing the disposition of all the vocal forces involved are printed in the CD booklet (see: http://www.navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6113/booklet---woefully-arrayed---jonathan-little.html ). Leading British polychoral expert Hugh Keyte argues that the lost potential of "the acoustics of performing spaces" is rediscovered in these works, and is impacting upon the aesthetic direction of new choral music.

For further details of the 2018 CHASS AUSTRALIA PRIZES, which are designed to honour distinguished achievements by Australians working, studying or training in the HASS (Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences) areas, see: http://www.chass.org.au/chass-media-releases/

International Polychoral Music Research, Creation and Recording Project (Jonathan David Little)

(external link)

AWARDS AND AWARD NOMINATIONS now received in the UK, US and AUSTRALIA:

* WINNER (UK): "ENCORE CHORAL" AWARD: BBC Radio 3 / Royal Philharmonic Society

* NOMINATION (USA): "BEST CLASSICAL MUSIC RECORDING": RoundGlass Global Music Awards 2018 (26th January, Edison Ballroom, New York)

* NOMINATION (AUSTRALIA): "CHASS AUSTRALIA PRIZE for DISTINCTIVE WORK": Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (29th Oct., Storey Hall, Melbourne)

FULL WORLDWIDE REVIEWS LIST NOW IN:

POLYCHORAL MUSIC RESEARCH, CREATION & RECORDING PROJECT

"WOEFULLY ARRAYED" (issued on NAVONA NV6113, 2017)

[USA, UK, AUSTRALIA, CANADA, ITALY, FRANCE]

Fanfare (USA):

* (1) ‘The disc of sacred and secular choral and polychoral music by Jonathan David Little, Woefully Arrayed … is nothing short of remarkable. Stunningly recorded, the pure sonic joy is visceral. On a personal level, I haven’t experienced such revelation in choral terms since the Tallis Scholars’ first recording of the Allegri Miserere. … Woefully Arrayed is a masterpiece … radiant … full and reverberant … magnificently handled … A superb disc … shot through with spiritual light and which speaks on a very deep level to the listener.’ – Colin Clarke, “The Profundity of Polychoralism: Exploring the work of Jonathan David Little” (extended interview), and “Little, Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Fanfare, Vol.41, No.2 (Nov./Dec. 2017) (USA)

* (2) ‘Jonathan David Little’s music walks the same path as that of Arvo Pärt and Morten Lauridsen … and Little’s style is natural and organic. He does not offer a contrived veneer of ethereality, but rather employs polychoral-inspired and spatial techniques to create a warm wash of sound with some substance behind it. … Little uses familiar musical materials and processes to craft music that is at once simple and complex. … The music’s underlying structures provide a solid framework compositionally, and Little is surely adept at writing for voices; this music is lush, relaxing and meditative. As enjoyable as the music is for listeners, I suspect that it is even more rewarding for the choirs. It is easy to imagine any one of the selections on this disc becoming a perennial favorite for choirs of all kinds, from amateur community choirs to professional ecclesiastical ensembles.’ – James V. Maiello, “Little, Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Fanfare, Vol.41, No.2 (Nov./Dec. 2017) (USA)

Audiophile Audition (USA):

* ‘This album is a delight on all fronts. … Little achieves unique and beautiful effects through spacing and arrangement of vocal groups. It seems that Little’s techniques are well grounded in both very careful construction of harmonies and voicing as well as in acoustics and the physics of sound. … In fact, two of the most fantastically beautiful works in this collection—Gloria, op.18 and Wasted and Worn, op. 6, also have atypical and unique placement of the singers. … Of the six selections herein, I would be hard pressed to pick a favorite … When I hear music of this sort it reminds in the best possible ways of when I have actually had the pleasure of hearing music by Tallis or Dunstable in a large old marble clad cathedral … The three groups performing here—Vox Futura, the Thomas Tallis Society, and The Stanbery Singers—are all amazing; some of the best groups you will ever hear. Very enjoyable, highly recommend!’ – Daniel Coombs, “Jonathan David LITTLE: Sacred and Secular Choral & Polychoral Works”, in Audiophile Audition, August 1st, 2017 (USA)

Cinemusical (USA):

Reviewing great classical and film music

Recording: ****/****

Performance: ****/****

* ‘One need look no further than the excellent essay by Hugh Keyte which appears in this new Navona release to further discover some historical perspective on this unique sound. … Each of these moments sort of bursts forth from the slowly-built verses in rather beautiful colors. … the stunning quality of the work … has this sense of coming into one central space only to go the far reaches of the space. Carefully-managed dissonance also adds to the emotional depth of the piece. … The album is filled with this rather engaging music … The polychoral approaches are managed well in the recording and in fact, the well-thought-out booklet even describes placement of singers for each piece. The overall production is rather stellar with excellent art work and overview of the style of music. It is a most fascinating release.’ – Steven A. Kennedy, “Polychoral Music by Jonathan David Little”, in Cinemusical, August 28th, 2017 (USA)

Choir & Organ (UK):

****

* “Little writes very much in the manner of the renaissance masters, creating what a modern sensibility would identify as ‘immersive’ music of strongly mystical aspect. That mysticism and muscularity can go hand-in-hand is confirmed by the title piece, which is reprised in condensed form at the end of the disc. … The pieces are performed in very different acoustics … [which] makes sense of the sacred/secular split and of the virtuosic disposition of voices.” – Brian Morton, “Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Choir & Organ (Nov./Dec. 2017) (UK)

Gramophone (UK/NORTH AMERICA):

* ‘The Australian-born composer has cast his resplendent sacred and secular pieces in the polychoral style of the Renaissance and early Baroque, calling for choral forces to be placed in various configurations and spaces to achieve the intended sonic and expressive effect. Although much of the impact can be discerned through speakers or earbuds, hearing them in an actual acoustic environment would add even more lustre.

The booklet notes include drawings of the different placement of voices, helping greatly to convey what Little intends. … What is most important is the music itself, which sounds at once ancient and modern. Little shows masterly command of the choral idiom in the luminous interweaving of voices and occasional solo flights. … The repertoire is performed by Vox Futura (Boston), The Stanbery Singers (Cincinnati) and the Thomas Tallis Society Choir (Greenwich, London), all of whom sound mesmerised by Little’s engaging music.’ – Donald Rosenberg [Editor, Early Music America], “LITTLE Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Gramophone, Vol.95 (Jan. 2018) [North American edition, “Sounds of America” supplement, iii] (UK/NORTH AMERICA)

Limelight (AUSTRALIA):

***

* ‘Little has been particularly influenced by the polychoral writing of the late Renaissance, which he blends with the often blurred, slow-moving harmonic architecture of minimalism. This style is further enhanced by resonant acoustics and an often high vocal tessitura to create a sense of the other worldly. This programme features sacred and secular works with performers from America (Vox Futura, Boston and The Stanbery Singers, Cincinnati) and England (The Thomas Tallis Society Choir, London). The most substantial piece is Woefully Arrayed, a 25-minute setting of an early Passiontide poem, in which the verse refrain structure allows for the alternation of varying textures and an effective, cumulative build-up of ecstatic utterances. … this is carefully crafted and considered music ... ’ – Tony Way, “Back to the future sees a postmodern take on polychoral” (CD review), in Limelight (Jan./Feb. 2018), p.97 (AUSTRALIA)

Kathodik (ITALY):

****

* “Tra le varie etichette che sono state affibbiate al compositore di origine australiana, ma ormai da tempo stabilizzatosi in Gran Bretagna, Jonathan David Little (classe 1965), quella di “minimalismo estatico” mi sembra la più appropriata, quanto meno in riferimento ai lavori corali presentati in questo notevole ? anche per ciò che concerne la veste grafica e il corposo booklet ? Cd della Navona. A partire dal brano che dà il titolo alla selezione, Woefully Arrayed, per proseguire con le altre composizioni sacre e profane, a colpire è innanzitutto la luminosità delle linee vocali ? anche laddove il tema è dolente ?, la cui ripetizione si arricchisce, gradualmente, di decorazioni strumentali e delicate increspature ritmiche. Il linguaggio armonico è principalmente modale, ma la scrittura di Little si avvale delle più disparate e raffinate tecniche, dalla “poli-coralità” di ascendenza rinascimentale ai contemporanei “cori spezzati”, che aggiungono effetti di avvolgente spazialità a una musica già di per sé emozionante e personale.”

[‘… remarkable … the first thing to strike one is the luminosity of the vocal lines … Little's writing takes advantage of the most disparate and refined techniques – from its "polychoral" Renaissance ancestry stem contemporary "split choir" procedures, which create effects of spatial envelopment within a music, which is, in itself, already intimate and exhilarating.’] - Filippo Focosi, “Jonathan David Little ‘Woefully Arrayed’” (CD review), in Kathodik (2nd November, 2017) (ITALY)

Music & Vision (UK):

* ‘trance-like … well-crafted and original … also features two fascinating secular choral works … This really is Australian music with a difference … sheer beauty. ’ – Keith Bramich, “Practical Experiments? …” (CD review), in Music & Vision (27th June, 2018) (UK)

Des Chips et du Rosé / Nova Express (FRANCE)

* ‘… c'est tellement beau’ [“so beautiful”] – (20th August, 2017) (FRANCE)

La Scena Musicale (CANADA):

****½

* ‘Little’s musical proposition is to write in the manner of polyphonic composers of the Renaissance such as Palestrina and Josquin des Prés.

However, Little is not content to imitate the language of his predecessors. He absorbs the general technical characteristics, like contrapuntal writing and melismas, but takes some liberties in his own writing by introducing, for example, strong dissonance between the voices. Additionally, Little is inspired by the Venetian tradition of polychoral singing, and creates dynamic interaction between different choral groups. … The composer also uses astute means of playing with the acoustic properties of the recording space. The placement of singers within that space is meticulously calculated to create certain sonorities. …

In summary, Little’s musical style is arrestingly beautiful, and manages to strike a delicate balance between tradition and innovation.’ – Arnaud G. Veydarier, “Jonathan David Little, Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in La Scena Musicale (Feb./Mar. 2018), p.32 (CANADA)

Review Graveyard (USA):

* ‘The sound is strikingly contemporary, yet also intertwined with choral traditions of the past ... Fans of choral music are in for a huge treat … Several of these beautiful and moving settings of profound and poignant texts feature intricate “polychoral” techniques: multi-part, multi-divisi, solo, echo and spatial effects. … This is a truly sensory rich album. You won't regret adding this to your collection.’ – Darren Rea, “Woefully Arrayed: Sacred & Secular Choral & Polychoral Works”, in Review Graveyard, 1st September, 2017 (USA)

Infodad (USA):

* ‘Kyrie and Gloria on this CD are both sonically impressive and show understanding of older vocal forms … On the secular side of things, Wasted and Worn, intended as a memorial to painter John William Godward (1861-1922), features some beautiful vocal writing …’ – Infodad (6th July, 2017) (USA)

iTunes (USA):

* ‘Another time, another place! When it comes to transporting you to a different place, WOEFULLY ARRAYED is in a class of its own! I’m taken to a faraway place and age with so much tranquility and peaceful feelings there, assisted by the smooth transitions in the music. It’s a lovely composition, beautifully performed with detailed dynamics keeping one gently engaged - lovely!’ – Grammy-Award winning composer and flautist, Wouter Kellerman (18th October, 2017) (USA)

WOEFULLY ARRAYED - CD Reviews received July to November 2017 (Navona NV6113)

(external link)

JONATHAN DAVID LITTLE

WORLDWIDE CRITICAL REACTION TO THE ALBUM

WOEFULLY ARRAYED (NAVONA NV6113, 2017)

Fanfare (USA)

• ‘The disc of sacred and secular choral and polychoral music by Jonathan David Little, Woefully Arrayed … is nothing short of remarkable. Stunningly recorded, the pure sonic joy is visceral. On a personal level, I haven’t experienced such revelation in choral terms since the Tallis Scholars’ first recording of the Allegri Miserere. … Woefully Arrayed is a masterpiece … radiant … full and reverberant … magnificently handled … A superb disc … shot through with spiritual light and which speaks on a very deep level to the listener.’ – Colin Clarke, “The Profundity of Polychoralism: Exploring the work of Jonathan David Little” (extended interview), and “Little, Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Fanfare, Vol.41, No.2 (Nov./Dec. 2017) (USA)

• ‘Jonathan David Little’s music walks the same path as that of Arvo Pärt and Morten Lauridsen … and Little’s style is natural and organic. He does not offer a contrived veneer of ethereality, but rather employs polychoral-inspired and spatial techniques to create a warm wash of sound with some substance behind it. … Little uses familiar musical materials and processes to craft music that is at once simple and complex. … The music’s underlying structures provide a solid framework compositionally, and Little is surely adept at writing for voices; this music is lush, relaxing and meditative. As enjoyable as the music is for listeners, I suspect that it is even more rewarding for the choirs. It is easy to imagine any one of the selections on this disc becoming a perennial favorite for choirs of all kinds, from amateur community choirs to professional ecclesiastical ensembles.’ – James V. Maiello, “Little, Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Fanfare, Vol.41, No.2 (Nov./Dec. 2017) (USA)

Audiophile Audition (USA)

• ‘This album is a delight on all fronts. … Little achieves unique and beautiful effects through spacing and arrangement of vocal groups. It seems that Little’s techniques are well grounded in both very careful construction of harmonies and voicing as well as in acoustics and the physics of sound. … In fact, two of the most fantastically beautiful works in this collection—Gloria, op.18 and Wasted and Worn, op. 6, also have atypical and unique placement of the singers. … Of the six selections herein, I would be hard pressed to pick a favorite … When I hear music of this sort it reminds in the best possible ways of when I have actually had the pleasure of hearing music by Tallis or Dunstable in a large old marble clad cathedral … The three groups performing here—Vox Futura, the Thomas Tallis Society, and The Stanbery Singers—are all amazing; some of the best groups you will ever hear. Very enjoyable, highly recommend!’ – Daniel Coombs, “Jonathan David LITTLE: Sacred and Secular Choral & Polychoral Works”, in Audiophile Audition, August 1st, 2017 (USA)

Cinemusical (USA)

Reviewing great classical and film music

Recording: ****/****

Performance: ****/****

• ‘One need look no further than the excellent essay by Hugh Keyte which appears in this new Navona release to further discover some historical perspective on this unique sound. … Each of these moments sort of bursts forth from the slowly-built verses in rather beautiful colors. … the stunning quality of the work … has this sense of coming into one central space only to go the far reaches of the space. Carefully-managed dissonance also adds to the emotional depth of the piece. … The album is filled with this rather engaging music … The polychoral approaches are managed well in the recording and in fact, the well-thought-out booklet even describes placement of singers for each piece. The overall production is rather stellar with excellent art work and overview of the style of music. It is a most fascinating release.’ – Steven A. Kennedy, “Polychoral Music by Jonathan David Little”, in Cinemusical, August 28th, 2017 (USA)

Choir & Organ (UK)

****

• “Little writes very much in the manner of the renaissance masters, creating what a modern sensibility would identify as ‘immersive’ music of strongly mystical aspect. That mysticism and muscularity can go hand-in-hand is confirmed by the title piece, which is reprised in condensed form at the end of the disc. … The pieces are performed in very different acoustics … [which] makes sense of the sacred/secular split and of the virtuosic disposition of voices.” – Brian Morton, “Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Choir & Organ (Nov./Dec. 2017) (UK)

Des Chips et du Rosé / Nova Express (FRANCE)

• ‘… c'est tellement beau’ [“so beautiful”] – Des Chips et du Rosé / Nova Express (20th August, 2017) (FRANCE)

Kathodik (ITALY)

****

“Tra le varie etichette che sono state affibbiate al compositore di origine australiana, ma ormai da tempo stabilizzatosi in Gran Bretagna, Jonathan David Little (classe 1965), quella di “minimalismo estatico” mi sembra la più appropriata, quanto meno in riferimento ai lavori corali presentati in questo notevole ? anche per ciò che concerne la veste grafica e il corposo booklet ? Cd della Navona. A partire dal brano che dà il titolo alla selezione, Woefully Arrayed, per proseguire con le altre composizioni sacre e profane, a colpire è innanzitutto la luminosità delle linee vocali ? anche laddove il tema è dolente ?, la cui ripetizione si arricchisce, gradualmente, di decorazioni strumentali e delicate increspature ritmiche. Il linguaggio armonico è principalmente modale, ma la scrittura di Little si avvale delle più disparate e raffinate tecniche, dalla “poli-coralità” di ascendenza rinascimentale ai contemporanei “cori spezzati”, che aggiungono effetti di avvolgente spazialità a una musica già di per sé emozionante e personale.”

EXCERPT IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION:

‘… remarkable … the first thing to strike one is the luminosity of the vocal lines … Little's writing takes advantage of the most disparate and refined techniques – from its "polychoral" Renaissance ancestry stem contemporary "split choir" procedures, which create effects of spatial envelopment within a music, which is, in itself, already intimate and exhilarating.’ – Filippo Focosi, “Jonathan David Little ‘Woefully Arrayed’” (CD review), in Kathodik (2nd November, 2017) (ITALY)

• Review Graveyard (USA)

‘Fans of choral music are in for a huge treat … Several of these beautiful and moving settings of profound and poignant texts feature intricate “polychoral” techniques … This is a truly sensory rich album. You won't regret adding this to your collection.’ – Darren Rea, “Woefully Arrayed: Sacred & Secular Choral & Polychoral Works”, in Review Graveyard, September 1st, 2017 (USA)

Infodad (USA)

• ‘Kyrie and Gloria on this CD are both sonically impressive and show understanding of older vocal forms … On the secular side of things, Wasted and Worn, intended as a memorial to painter John William Godward (1861-1922), features some beautiful vocal writing …’ – Infodad (6th July, 2017) (USA)

iTunes (USA)

• ‘Another time, another place! When it comes to transporting you to a different place, WOEFULLY ARRAYED is in a class of its own! I’m taken to a faraway place and age with so much tranquility and peaceful feelings there, assisted by the smooth transitions in the music. It’s a lovely composition, beautifully performed with detailed dynamics keeping one gently engaged - lovely!’ – Grammy-Award winning composer and flautist, Wouter Kellerman (18th October, 2017) (USA)

FANFARE 2017 INTERVIEW: The Profundity of Polychoralism: Exploring the Work of Jonathan David Little

(external link)

Second Interview in Fanfare (US): Feature Article in Issue 41:2 (Nov/Dec 2017)

"The Profundity of Polychoralism: Exploring the work of Jonathan David Little" BY COLIN CLARKE

The disc of sacred and secular choral and polychoral music by Jonathan David Little, Woefully Arrayed (review below), is nothing short of remarkable. Stunningly recorded, the pure sonic joy is visceral. On a personal level, I haven’t experienced such revelation in choral terms since the Tallis Scholars’ first recording of the Allegri Miserere. As an interviewee, it turns out, Little is every inch as fascinating as his music. The following in-depth interview may be seen as an indispensable complement to the listening experience itself.

Your history was traced in Martin Anderson’s interview in Fanfare 36:1 (2012), so this time we’ll be concentrating on your most recent disc on Navona, “Woefully Arrayed”. You talk in that previous interview about the importance of accessibility, and the music on the new disc has an instant appeal. Yet you balance that with a depth that has variously been called “ecstatic minimalism”, “antique futurism” and “picturesque archaism”. How do you react to those labels (and labels in general, for that matter!)?

When you embark upon your first compositions, and are building a compositional career, nothing could be further from your mind than how, one day, audience and/or critics might begin to “define” your music stylistically. I don’t think you even consider terribly closely the “tradition” or “school” to which you belong. Indeed, in our unique age in the history of music?that is, having arrived at a time when we can begin to hear and appreciate the music and techniques of many past eras and indeed various geographical locations as well, it is not surprising that some composers are becoming exceptionally eclectic. As a composer, you do tend to draw from all the best and most striking models as you build your own technique, and then, one day, when quite a few of your works can be heard, the “receptors” of your music inevitably begin to insist on knowing how your music might be defined; and we do live in an age when everything, it seems, must be classified according to its genus––artistic or otherwise (and this certainly also aids some aspects of the commercialization of music). Did the Impressionist painters want to be known as “Impressionists”? Most likely not. They might?if forced?have perhaps chosen a name that allied innovative concepts of color and texture with those relating to the fleeting and changing nature of light across time. But then, they may consequently have chosen a name far too complex to be instantly appreciated by the pubic! I don’t think it is often therefore the composer who chooses the label, or “ism”, with which, ever after, they tend to become associated.

As to the labels thus far applied to my own “brand” of music, they may not even have settled down yet; equally, I am not unhappy with those that have been applied, in the sense that they may convey some initial ideas of what the music might be like. Wonderful labels such as “antique futurism” (compliments of an Italian music critic, who favors marvelously florid language) are at once accurate, but at the same time could be confusingly contradictory for a novice listener. “Picturesque”, “archaic”, “minimalist”, “ecstatic”?these are all accurate to some extent, but can they cover the entirety of techniques and soundworlds of a composer’s body of work?

I do, however, think that no matter how chameleon-like and eclectic a composer is, there should still be a unity or unifying principle of general style and sound within each individual work, and certainly a reasonably distinctive language overall in which the composer speaks (and this is the great challenge of our time, to forge from so many elements a flexible and coherent language that is also capable of true profundity). “Finding your voice” as a composer will generally only emerge over a relatively long period of time. I think I was about 40 years old before I knew I had matured enough artistically to feel confident in my own technical language and its resulting sound but I hope it keeps evolving, as I keep writing and learning, in an endless cycle.

Artistic labels are perhaps for the world to decide. I can’t even now think how best to describe my own music. You might equally ask what it is that is most important to me as a composer, and work outwards from there. For me, this embraces concepts such as beauty of line, of constantly-building intensity in a certain direction, and of gorgeousness of sound––all adding up to the overall goal of transporting the listener that other, “higher plane” of our existence?redeeming the time, you might say, so that we can be reminded of the deepest and truest of things, and aspire to reach towards the finest of all our qualities; for we might otherwise today drown in the ever-present mundane (which, I think, Flaubert was already railing against, well over a century ago) or sink under the weight of the depressingly constant barrage of news of the world’s many tragedies. Perhaps this is indeed escapism towards the ecstatic? But surely that is what is needed now, more than ever, in what could become a very “cold” and bland world, without the necessary balance of exposure to the most humanizing and civilizing qualities of the arts. Therefore, besides technical accuracy, I also want the emotional heart of the music to come across in performance, and in recordings however “classical” in construction (conservatively constrained), and irrespective of the level of symmetry and refinement, in any particular work. We still need the sort of passion that we seem to be in danger now of losing, largely as Aldous Huxley foresaw in Brave New World. I hope we have achieved a reasonable balance in this regard throughout the current album, for I am always a fan of rubato and other unwritten freedoms, wherever the music requires (and it very often does), for best and most visceral effect. It is impossible to indicate every nuance when producing a manuscript; indeed, a manuscript documenting every single nuance would be ridiculously cluttered, and consequently unreadable!

An integral part of your expressive vocabulary is polychoralism: the spatial arrangement of choirs and the use of that as a vital part of the compositional process. The idea, therefore, becomes far more than an effect; it is an integral part of the musical statement. Can you trace your fascination with this method of writing? And how it came to mean so much to you?

When allied to other technical devices, the deployment of choral and/or instrumental forces within a particular space is an important and sometimes overlooked component of a work’s effect upon the ear: sounds can emerge from left/right, forward/behind?and, to use an analogy with painting?foreground, midground and background. In opera, such spatial effects have routinely been used for years (besides performing on the move, of course), and these effects have spilled over into symphonic works, too. One need only think of straightforward examples such as offstage bells and cowbells in Mahler’s work, or Holst’s brilliantly atmospheric use of offstage women’s chorus in “Neptune” from The Planets. And then, into this mix, you can also add devices such as larger forces versus smaller forces, and have single instruments or voices pop up as well, like individual specks of light or color.

In adolescence, hearing Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis for double string orchestra first awoke me to such possibilities. (And this piece also incorporates string quartet, so that it, in fact, comprises three different “sizes” of performing groups.) In such works, the forces, and their deployment, are an essential part of the overall effect, especially within a large, cathedral-like space (the first performance in this case being in Gloucester Cathedral). The evocative and luxuriant harmonies resound and interact throughout the space in a cleverly-calculated way. Yet it is interesting to note that Vaughan Williams still subsequently felt the need to revise this work twice, for purposes of both tightening the structure, and further refining the sound. One can almost think of the venue itself as a special type of overarching “instrument” or “sound body”––and one that needs to be mastered, tuned and played well, like any other: and naturally this will involve determining where the various forces should most appropriately be placed.

The Kyrie on this present album was my first experiment with the sounds of double choir and soloists floating around a large, resonant space. (Its first performance was in Waltham Abbey––where Tallis worked––as part of the 500th anniversary celebrations of his birth.) The use of double choir imparts a left/right “stereo” effect, while the two extra groups of soloists (SA + SSA) add further twin sound sources as they echo across high balconies. I envisioned these soloists as constituting a physically higher-level stereo addition, though the conductor, Philip Simms, had a slightly different idea. While he did choose to place the soloists side-to-side and above the double choir, he positioned them well behind the audience. The effect was completely unexpected, disembodied and striking. This proved to me that while a composer should aim to suggest an ideal layout, there may be other equally valid possibilities for the deployment of various forces in “polychoral” works?as best suited to a particular venue (that oft-forgotten, but ever-present “instrument”). The practicalities of musical acoustics must be the determining factor here. Real problems can emerge when forces are placed too far apart, and/or where the performers have difficulty in hearing, blending, keeping in tune, or following the rhythm in conjunction with other sub-groups of performers. Hugh Keyte believes that the performance of one very ambitious late Renaissance polychoral work failed spectacularly precisely because of such reasons?and there is also evidence to show that sub-conductors were required in some quite complex late Renaissance and early Baroque works, this being the period when “polychoralism” rose to its ultimate heights in terms of sophistication, before subsequently falling out of fashion.

As the Kyrie was such a success in terms of my early choral works, I determined upon two things. Firstly, that the deployment of choral and/or instrumental forces in designated spatial configurations ought in many works to be considered more closely by a composer (as one of several elements in fashioning a new composition). And, secondly, that I would like to find out more and pursue writing a set of choral works exploiting the range of techniques permitted by such subdivision of forces and spatial configurations. Happily, the Australia Council invested in the writing of these works, and the peer reviewers of my initial proposal to the Council also seemed intrigued as to the possibilities. And so it was that the Australia Council approved the writing and recording of a series of works that would feature intricate “polychoral”-inspired techniques: multi-part, multi-divisi, solo, and unusual spatial effects (a mode of working labelled cori spezzati?literally “split” or “separated choirs” ?as the technique was referred to in the Renaissance and early Baroque periods).

Having written Wasted and Worn as the first of three major new works, I found I had then to pause and undertake a further and much deeper “research” phase, since I realised there was much I still did not know about the whole armoury of techniques upon which so many brilliant Renaissance polychoral composers had once drawn. I put to Robert Hollingworth this question:

“Being in the midst of an international project related to writing and recording contemporary choral and "polychoral" works (for which I am also now trying to construct diagrams to illustrate how, for best effect, these works could be performed), I am wondering what, and how much definitive evidence, actually exists as to where exactly the performers may have been spatially positioned when originally performing Renaissance works …”

“Actual evidence?” he queried. “Practically nothing. However Hugh Keyte has thought about this long and hard …”. I can remember being more than a little shocked that we seem still to know so very little about all this, and it was to Hugh Keyte that I turned for advice, and for clues. (He also kindly agreed to write a contextual essay on “polychorality” for the CD booklet?which is a useful starting point for beginning to understand some of the issues involved.) It dawned on me that the Renaissance must have been an age of the rediscovery of multi-dimensional artistic perspective not only in visual form (as with “linear perspective”), but in aural form as well (since the more ambitious composers seemingly experimented with different types of sonic placement, aural “depth of field”, and other such effects, all related to the perception of sound in space). Continued research is unearthing facts about the hiring and placement of performers in Renaissance music, but, of course, even beyond that, I want to know how the composers themselves thought, and ultimately almost to try to isolate and understand each and every one of the various forgotten techniques and myriad possibilities involved in writing for multiple groups of forces at once.

It is like being the musical equivalent of an archaeologist: we dig up a bare few clues from archival records, or from scores, and from these, then try to reconstruct a whole vanished compositional and performing tradition. All I can say is that some of the works on this CD begin to go some little way to reclaiming the lost potential of performing spaces?and rediscovering an esoteric form of compositional knowledge that has, in large part, now been lost. I would still like to learn so much more! But such knowledge is never so that I can write “old”-sounding music; rather, it is so that I can add a valuable extra resource to my compositional palette. In all of the works that I explored in order to find technical precursors, only the Dedication Service for St. Gertrude’s Chapel, Hamburg, in 1607 (see the edition edited by Frederick K. Gable, published by A-R Editions) retains comprehensive documentation as to where instrumental and vocal forces were placed during the actual performance?in that particular case, literally producing a sort of “surround-sound” effect around the auditors. You will, therefore, see that I have made a point to include very thorough diagrams in both my musical scores, and in the CD booklet, as to where my performers should best be positioned (complete with any possible alternatives). In 400 years’ time, I don’t want there to be any wildly speculative debate about where my performers ought to be placed!

How do you decide on the layouts? Is it to do with the acoustics you are writing for, indeed specifically for the place of the work’s premiere? The booklet to the Navona release helpfully gives diagrams for Gloria, Wasted and Worn and That Time of Year, and they are all individual.

To begin with, the type of work it is, and the text, together first suggest what spatial arrangement may prove most appropriate for a new work?at least on a general level?and so it evolves from there. Of course, this necessarily involves envisaging the ideal performance venue and acoustic for each work. I believe that Benjamin Britten always kept in mind his performance venue when he was writing, and it is clearly important to do so, wherever that is possible. But, if you are writing more “speculatively” shall we say, and there is no guaranteed performance venue, and/or the work might, or could, be performed in a variety of different types of venue, then one’s imagination and experience must come even more into play in trying to ensure that the effect, in performance, will be largely as intended. (This also assumes that some venues will not be terribly appropriate for particular works?and a good conductor or programmer should be able to factor this aspect into their thinking, besides other obvious considerations: of forces involved, complexity, style, contextual interest, and the order amongst other works, and so on.)

Venues also affect how a work is performed. To take one simple example, Woefully Arrayed will need to move more quickly in a smaller performing space, or it will seem to drag and lose onward momentum (always bearing in mind that it will probably not be very effective in a less than medium-sized venue). But in a very large, resonant space?and especially with bigger forces, too?Woefully Arrayed can be taken at a more leisurely pace (really quite lento), and yet it will not seem at all slow in this circumstance. A larger venue will, moreover, allow for the full range of subtleties of overlapping/mingling lines and echoes to be appreciated, so increasing audience appeal, as the several groups of sounds initially emanate from particular directions, then travel around the entire space in interesting patterns on beguiling journeys that circumscribe the listener.

The final layout of the forces involved in these vocal works will have involved many rounds of fine-tuning as the work progresses (not least to make sure that any individual performers required are to be found in the right place at the right time, especially where there has been some movement of the singers away from their original positions?as there is, indeed, in both Wasted and Worn and That Time of Year). The final layout for Wasted and Worn indicates all of the physical movements, both large and small: whether simple displacement from the original position (and return), or merely a very subtle quarter-turn round and away from the audience (so that the singer sounds a touch more distant?but not nearly so distant as being initially placed, or subsequently moving, much further away).

I’d like to ask about your relationship with the past. In the op. 18 Gloria (“Et in Arcadia ego”) you quote an anonymous 14th-century three part setting of “Ave maris stella,” a setting itself based on an even earlier chant (at least to the ninth century!). Is the past an inspiration? Or a building block? Or something to meditate on? There’s almost a Russian doll element to that piece, you take off one layer of reference and reveal another one!

The past is treasure. The past may be “a foreign country”, but it is also treasure?often just waiting to be discovered. It is an inspiration, a source of all manner of wonderful technical devices (concerning which I have always been eager to learn); and it is a vital starting-point for the new, always informed by the very best of past workmanship. Instrumental and vocal technologies and capabilities may change through the ages, but many techniques of musical composition are merely recycled and reinvented, in different ways. And, of course, the balance and type of the total musical parameters, or components, employed in a musical composition (consisting of elements such as melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, structure, dynamics, orchestration, special devices, etc.) re-evolve and are refashioned in differing proportions, and are given new emphases of importance, so to produce seemingly brand-new “flavours” from the age-old ingredients within. Emerson’s marvellous essay Quotation and Originality pretty much summarises my beliefs philosophically in this regard. Emerson maintained: “We cannot overstate our debt to the Past, but the moment has the supreme claim. The Past is for us; but the sole terms on which it can become ours are its subordination to the Present.”

I have recently started using the phrase “historically-informed composition” ?as a complement or counterpart to that well-known phrase, “historically-informed performance” ?and as a way of emphasizing the fact that few compositions of any style are truly radically “new” underneath. This “historically-informed” label also stresses the importance of making a lifetime study of musical techniques, and indeed the musical techniques of all ages, if one truly wishes to master one’s craft?especially in an era when it begins to seem as if anyone can easily become a composer, or indeed artist of any type, without the long years of study and contemplation of past models necessary ultimately both to develop one’s own expressive language, and to find ways to evoke the deepest of messages that have at least some chance of resonating across the ages. It is for me almost a moral imperative that any serious composer today should aim to absorb all past traditions, whether stemming from the Middle Ages (including any techniques well enough understood even from before that?together with the remnants of long-established folk traditions), or whether derived from the Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic or “Modern” periods. It may also prove helpful to seek inspiration in the music of cultures reasonably alien to one’s own, provided that such “spice” still sits comfortably within a (novel) stylistic whole.

And your Russian doll analogy is quite apt: inside the music may be many archaeological layers, wherein are to be found much older techniques and references. The “outer” layers may point to something quite new in sound?while the creator’s skill is, in some way, often thoroughly to blend and to conceal what lies within!

The more outward-going side of you is evident in the Polyhymnia disc Martin Anderson talked to you about last time (“Terpsichore the Whirler” is wonderfully extrovert, as is the brief “Fanfare”); yet even here, the intensity of “Polyhymnia” is like an orchestral version of the choral glories of your disc, the Olomouc orchestra strings absolutely radiant. Would you see ecstasy as at the core of your music?

I would agree that much of Terpsichore is certainly less “cerebral” than several of my other works! Terpsichore aims to create a “whirling kaleidoscope” of orchestral colors and textures. Yet even that work should ideally raise our spirits to exuberant heights. Perhaps it might indeed be construed as a more extrovert manifestation of the “ecstatic”.

For many years, I did not use or apply the word “ecstasy” to my works in any way, but the concept admittedly does embody an important principle in terms of the purpose of much of my music, which is to uplift the listener, and so has much in common with religious or spiritual paradigms of reaching towards the ecstatic and transcendent. If I may make a couple of rough parallels with fine art and sculpture, there is an aspect of what I do that might be likened to a kind of intense, modern Pre-Raphaelitism in music, or even be considered “Bernini-like” ?in that it aims to encapsulate certain qualities of refined power and poignant ecstasy?a feeling that is at one and the same time both religious and sensuous: hence I find it necessary to insist that there must also be deep passion at the heart of creating such “radiance” (another descriptive word which seems perfectly appropriate––as do terms such as “ethereal”, “otherworldly”, and “visceral” ?all applied by various critics over recent years).

The earlier disc also included the Kyrie from Missa Temporis Perditi, a Mass which I believe is still in progress? I wonder if this idea of not having to rush a work, of the music being in process and coming when it’s ready, is a reflection on the sense of timelessness your music itself exudes? In fact, the Kyrie op. 5 was first sketched in 1985 but only completed 20 years later, is that right? Is there any projected finish year for the Missa?

At the heart of what you say lies an interesting question, and one that I’m not sure I can answer exactly. All artists tend to work in different ways. I have certain overall aims in terms of projects I would like ultimately to complete, but several of them seem so potentially vast in conception that the only way sensibly for me to deal with them?and maintain quality?is indeed not to rush them. The only real downside of this approach, working sometimes over several years, is that there may be a danger that the many components of a large-scale work completed over long time periods may not always fully cohere stylistically. I try to avoid this, where possible, by sketching initial ideas for the whole. You will have noted in the CD booklet that it also mentions how opus numbers are accorded to my works chronologically by date of conception, rather than completion. This can result in what seem like strange anomalies in terms of a creative timeline, but I believe it forms the truest record of one’s work. (This also provides the reason why pieces belonging to the same series may have quite different opus numbers.) The Kyrie was first sketched out (in this case, in quite some detail) almost twenty years before the opportunity presented itself to refine and complete it for a specific purpose. Happily, with The Nine Muses series of large-scale instrumental works (and perhaps voices might yet also be involved in some capacity), the issue of stylistic unity is not so much an issue, as each one of the Muses will have a completely different character?illustrative of their unique attributes, or “personalities”!

I have tried to move more quickly on bigger projects, but they involve such detailed concentration over such extended periods of time that it is just too exhausting to work in that way for long. What you hint at is true: some works come when they come, and when the time is right?and most are best produced after long cogitation, technical trials, revisions and refinements. For the current project, even creating and recording three new, fairly large-scale choral works of differing types over two years (in addition to recording two others pre-existing) was quite an intense experience, but would never have come about so quickly had it not been for funding from the Australian Council. This funding made it possible, but also entailed some fierce deadlines––and deadlines do not always sit comfortably with creative necessity. Having said that, the other extreme then rears its head: the fact that the five-or-so-section Missa Temporis Perditi might be forty years in the making from the date of its first conception, while the nine movements of the Nine Muses may ultimately take twenty or thirty years?which, I admit, sounds an outrageously long time! Perhaps I can comfort myself with the fact that Leonardo da Vinci took the entire latter part of his life to produce his Mona Lisa, or that the artist-technician A.-L. Breguet’s “Marie-Antionette” watch was only completed 44 years after he first accepted the order (though unfortunately he didn’t quite live to see it finished). (Both of these examples constituted true labors of love?involving great self-challenge, and astonishing technical brilliance.) So, no, there is not yet an end date in sight for some of my “series” works. But when the time is right for each, and as the opportunity presents, I hope to turn my attention to every one of my works-in-progress, and will, one day, declare them complete!

There are other practicalities and exigencies, in addition, of course, two of which?my university teaching, and my interest in writing and documenting various aspects of music concerned with inspiration and technical innovation?also occupy my time. But all these tasks essentially complement, and, I trust, enhance one another. I have had two substantial books published in recent years (again, I’m afraid, two decades from first conception!): The Influence of European Literary and Artistic Representations of the 'Orient' on Western Orchestral Compositions, ca. 1840-1920: From Oriental Inspiration to 'Exotic' Orchestration (2010), and Literary Sources of Nineteenth Century Musical Orientalism: The Hypnotic Spell of the Exotic on Music of the Romantic Period (2011) ?for which I agreed to work with a publisher who did not wish, or economically need, to cut, abridge or otherwise edit the text, to delete any of the illustrations, or to disturb the layout. This consideration was very important to me. And with regard to my writing, I intend next to compile a “menu” of compositional devices (another long-term project!), which can be used as a sort of aide memoire of technical devices for working composers, just as much as for students of composition?and which may have the additional function of encouraging a broadening of the pool of techniques upon which a composer may draw. All these studies help me to understand past musical traditions and practices.

But none of this quite answers your question about the perceived “sense of timelessness” in some of my works?though perhaps having free rein over the length of time needed for any production may assist in generating “long-lived” works. Speed is often the enemy of intricate creation and perfection of form.

There are most certainly aspects of works such as Polyhymnia, Woefully Arrayed, and Gloria that do seek almost to disrupt and defeat time: to find the stillness at the center of the music, and, just occasionally, to lose all sense of “pulse”. (This is a dangerous artistic conceit, since almost all musical compositions depend upon some internal onward impetus in order to maintain their fluidity and direction, as well as the development and transformation of their materials, and indeed often merely a sufficient sense of evolution so as to sustain even the slightest interest.) Undoubtedly, such moments of seeming stillness are a reaching for ekstasis?a sense of mystical self-transcendence, a “standing outside oneself”, here mediated by the creator/artist. Can we indeed fashion such a thing as a “dynamic stillness” ?and, in doing so, use art to defeat time?that single (undefinable and incomprehensible) concept that would appear to be the barrier to immortality? (Or, at least, can we seem to do so, and create a representation, or simulation, of timelessness?) This is an element of the unique bond between the spiritual and the artistic, and, I think, at the center of what true religion and art ultimately seek: by some means to negate time and to latch on to the Eternal. The greatest of all our art-works seem to function as momentary gateways to the pseudo-Eternal in some way?though such moments may also be evoked through contemplation of nature, or upon sudden recognition of the generosity of the human spirit. Musical notation and other artistic symbols (all functioning like some mystical, arcane language), when decoded and revivified by us, can undeniably lead us to rapture, and open up those rare and precious moments of “epiphany,” in which we perceive important connections and meanings that may unite with other such transcendent experiences glimpsed at various stages along, what might be termed, our “circumambulatory journey” through life. (While we always tend to think of both life and music proceeding and steadily progressing in a straight line, as time passes, I doubt this is a truly useful way to regard such experiences, and so favor the notion of seeing life and art more as a meditation, from different perspectives, upon the whole.)

Your new disc is neatly divided into “sacred works” (opp. 13, 5 and 18) and secular works (opp. 6 and 2), so I’d like to move on to the latter if that’s OK: The secular “Wasted and Worn” (op. 6) is at once a tribute to the artist John William Godward (1861-1922) and to all artists who follow their muse irrespective of contemporary tastes and fashions, often leading to obscurity and indeed in Godward’s case, suicide. Godward’s paintings are now labelled as “(Victorian) neo-classicist,” but they certainly weren’t recognised to the extent they could have been in his lifetime. And there does seem to be an especially mournful quality to your piece, with its tightly-knit harmonies. It is also a more general tribute to those artists who toil away, unrecognised: would you like to elaborate on all of this, perhaps? How did the underlying premise affect the way you wrote the piece, either in harmonic terms or in terms of construction?

I found the text very apt, and quite affecting, on several levels. “Wasted and worn that passion must expire, / Which swept at sunrise like a sudden fire …”. The verse is an excerpt from A Parting by John Leicester Warren. It can be read in terms of romantic meaning, of course, but also in creative terms, as referring to the fire of inspiration and enthusiasm when all ideas begin to come together, and a new work starts to be forged (in the same way that Elgar quotes Shelley in the published score of his Second Symphony: “Rarely, rarely, comest thou, / Spirit of Delight!”). Warren’s verse succinctly charts the inevitable end of that process, and indeed seems to sum up the result of a lifetime of artistic work?when work has been generally unappreciated during the actual years of its creation: “His footsteps foiled, his spirit bound and numb, / Grey Love sits dumb.” It is not hard to find examples of creators of all types who would have felt themselves, in worldly terms at least, to be largely failures (though they will probably not have thought so in terms of the richness of the nourishing, necessity-driven life of the mind and spirit they will have lived, and all that they will have learned and experienced): think of Van Gogh, and even the sombre and solitary Warren himself (indeed, are many aware of his work at all?); but it struck me that John William Godward seems to epitomize such appalling vagaries of fortune. The contrast between how much Godward’s work is valued (quite literally) and admired today, and generally how very little it was during his lifetime, is fearsome. Added to that, his own family and relations so despised his art, his career, and his conduct, that they subsequently sought actively to obliterate his memory?including destroying all known papers, and every single photograph. And, as if that were not enough, following a lifetime of largely solitary work for this shy and hardworking, but prodigiously talented individual, and having at last achieved great heights of technical perfection (that incorporated many thousands of hours of the most painstaking detail of a type that few have matched before or since), a sudden stylistic revolution in the early twentieth century caused his entire opus to be regarded, almost overnight, as old-fashioned, “insipid”, and thoroughly undesirable.

At least a little public recognition is needed to nourish an artist’s often fragile spirit, and to help him or her find the courage to trudge on, and create again, no matter what the knock-backs; but to keep on going and live your ideal in so hostile an environment is utterly extraordinary?and, moreover, to pursue those ideals so steadfastly, not even knowing if any of those people that come after you will feel even the slightest benefit from your creative legacy. Yet it is precisely upon such individuals that the progress of art, and life, depends; it is through them that a record of beauty is made and bequeathed (whereby also the finest aspects of the human soul are preserved) ?to be passed on to, and so nurture, subsequent generations. This also reminds us that it is rarely or solely the famous names of the day that posterity selects as most treasured inspiration for those that come after us, but often just a few very hardworking, lesser-known individuals, who toil away incessantly, driven by inner necessity, and the fire of a great, almost holy light. They manage to embody the finest experience and ideals of their era, which, at rare intervals in their own lives, they have been fortunate and gifted enough to perceive, to comprehend, and to codify in terms of their art. Time transforms their work into future inspiration, and so nourishes those who are yet to be born. Such precious souls become our artistic Cassandras: we pay homage to their work and memory when they are gone, but so often misunderstand, ignore, and even deride all they create within the very era of the formation of their art.

As to Wasted and Worn itself, I sought to try to capture several passing episodes of different hues within the overall melancholic and poignant mood, united by the recurrence of a strange and haunting refrain that periodically surges up and fights against “the dying of the light”. Soon after the opening, the music reflects upon some uncomfortable inner thoughts, but never fails to revive?albeit briefly?and to reminisce upon recollected moments of great beauty and brilliance.

I had some trouble fashioning the whole of this work, and on completion remained for some time quite uncertain about it. It is only now, after several months, that I begin to think that there may be some enduringly powerful and worthy elements within. An uncomfortable text will put you through the emotional mill at the time you come to deal with it, and may leave you more than a little unsettled and unsure about it for a good while afterwards.

The Shakespeare setting (“That Time of Year”) sets Sonnet No. 73, a sonnet infused with the melancholy of the passing seasons. You score this for three male voices against two female ones, and Gesualdo has been linked to this piece in mood. It also includes some performer choice (the phrases of the middle section) and a “mobile” element (in this middle part, low male voices move to the centre while all others move backwards to produce a framing arc). Is this element of choice something you have used much? Or will in the future? The “drama” of the choral participants’ moving around the stage seems entirely apposite to bringing these texts to life …

Also, it’s a nice link that Shakespeare and Gesualdo are near-exact contemporaries. Was that a deliberate linking in your piece?

The piece That Time of Year was given a workshop performance by the BBC Singers in October 2016, and I pay tribute to Judith Weir for her advocacy on my behalf in asking the singers to practise exactly the movements you describe. But she was unsuccessful! Perhaps they felt there was not enough time to incorporate the movements, and/or it was too easy to trip over the staging, and/or the choir were not used to such demands, and preferred solely to concentrate on getting the notes right! This proved a lesson in itself about resistance to innovation and unwillingness to “perambulate” if you are a usually static choir. Yet some groups have in recent years been starting to experiment with this, and, of course, opera singers do it all the time. It does make me think more of reserving the use of movement for dramatic works, perhaps?though, I should say that having witnessed an American choir (the Chamber Choir of Christopher Newport University) undertake well-rehearsed choreographic movements in both That Time of Year and Kyrie (during a performance at the Ferguson Center for the Arts in Virginia, earlier in March 2016), it undoubtedly does add significant interest and impact both aurally and visually. Even watching the singers neatly changing positions between the works creates a splendid sense of curious anticipation as to what might be coming next! Likewise, the “aleatoric” middle section of That Time of Year tends to prove a challenge for most performers, and needs decent rehearsal time to make it a success. Here, some “live creativity” is handed over to the performers, and this is a mode in which they are not often used to working (so should, perhaps, be used sparingly, and with caution).

The linking of Shakespeare and Gesualdo was a happy coincidence, but it was very apt that some inspiration from both filtered through into That Time of Year, in order to help evoke both the mood of the text, and the spirit of the period.

How’s the muses project going? You said in your previous interview you were working your way through them in the “established” order. And related to that, can I ask you about plans for compositions going forward? And upcoming premieres and subsequent recordings?

I have sketched out plans for a couple more of The Nine Muses. I also aim in the immediate future to complete one or more further works for string orchestra, also the odd choral work whenever possible, as well as working on the book of compositional techniques that I mentioned earlier. (A disc of string works, before long, would be good, too!) Perhaps I will turn my attention more now to dramatic works, as well. Initially, I have in mind a sort of opera-ballet project, but will not elaborate too much about it now, since laying ideas bare at an early stage before they are fully conceived seems to me somehow to detract from their ultimate richness, by robbing them of their mystery and true potential.

Perhaps the way I proceed with my works is a little odd?which is to say that I do try, where possible, to have them “preserved” in published and recorded format as soon as they are completed, sometimes even before they have been premiered in performance. Historically, of course, the reverse has tended to be the case: works are only recorded after several performances. I think I pursue publication, and especially recording, in order both that nothing should be lost that might be worth preserving, but also so that there might be an initial “reference recording” of each work for audiences, performing groups, and conductors to hear (at which point I then tend to lobby for performances). One can also learn much from close listening to recordings of one’s music. I should also state that any first recording made does not necessarily represent what might be a best or “definitive” version, although, in the case of the works on this disc, they should, I hope, act as an excellent and stimulating starting point. In truth, perhaps the “ideal” performance is only ever heard in a composer’s head …

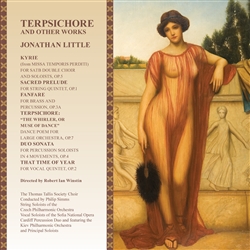

LITTLE Woefully Arrayed, op. 131 (two versions). Kyrie, op. 52. Gloria, op. 183. Wasted and worn, op. 64. That Time of Year, op. 24 ? 1,3Andrew Shenton, 2Philip Simms, 4Paul John Stanbery, conds; 1Heinrich Christensen (org); 1,3Vox Futura; 2Thomas Tallis Society Ch; 4The Stanbery Singers ? NAVONA 6113 (69:54)

Described by my colleague Lynn René Bayley as “a major new, original, and quite brilliant classical voice” (Want Lists 2008, Fanfare 32:2), Jonathan David Little is a composer whose music is vital, urgent and yet somehow timeless at the same time. Reviewer Martin Anderson, in interview with Little (Fanfare 36:1), described the music as “ecstatic Minimalism,” and I can see no reason to argue. According to the composer’s own website, alternative descriptions of his works from European critics have included “antique futurism” and “picturesque archaism.” Despite the multiplicity of recording venues (mainly US, the op. 5 Kyrie being the exception, taken down at the Church of St Alfege in Greenwich, UK), there is a blissful homogeneity here in terms of recording standard.

At some 25-minutes duration, Woefully Arrayed (with an alternative title of “Crucifixus pro vobis”) has a mesmeric element to it, the refrain earning more and more elaboration as the composition progresses. Choral layouts are helpfully given in the excellent booklet, which also includes a superb essay on polychoralism by Hugh Keyte. That essay refers to Tallis’ Spem in alium and how the different subdivisions of the choir might have been laid out spatially, an aspect viscerally brought to light this concert season in London where Vladimir Jurowski conducted a performance of the Tallis in half-light with choirs spread around the Royal Festival Hall; a blaze of light (literally) following the end introduced the opening of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony. Little plugs directly into the ethos of polychorality. His Woefully Arrayed is a masterpiece of time-stretching. As lines float and interact throughout the soundspace, there is a distinct impression of atemporality, of altering the way the listener experiences time. There is an abridged version (starting at the Third Refrain) that concludes the disc, lasting twelve minutes instead of 25; the effect in a complete play through of the recital is of a sort of homecoming. It has a real point in giving the impression of a cycle gaining completion after the wonderings into other territory, and twelve minutes is just enough to once more submit to the work’s hypnosis.

The Kyrie on this disc has an opus number of its own but is actually from the Missa Temporis Perditi (a work which is yet to be completed). For double choir with SSA and SA soloists, the piece requires a minimum of 22 singers and includes a short passage utilizing off-stage voices. This is the recording in Greenwich, just prior in fact to the work’s second public performance, in November 2005. The actual sound is superb, full and reverberant without smudging. The Thomas Tallis Society Choir is in fine fettle. The Gloria is from the same source, even though it holds a separate opus number and is currently described as a “companion piece.” Little inserts a very short quote from an anonymous 14th-century setting of Ave maris stella, itself based on a chant dating back to at least the ninth century. Recorded some twelve years later than the Kyrie in Boston, MA, this is slow-moving and poses huge challenges to the upper echelons of the choir, all magnificently handled here. The highest voices cope superbly with the Gloria’s radiant close.

The next two pieces are secular works and are performed by The Stanbery Singers. The first, Little’s op. 6, uses texts by Thomas Gray (the 1751 Elegy in a Church-Yard, as head-quotation) and John Byrne Leicester Warren, Lord de Tabley (the poem Wasted and worn that passion must expire). Little’s imagination is more focused on the gesture here, enabling more of a feeling of unfolding narrative. It is to a Shakespeare Sonnet that Little’s op. 2 moved to: That time of year thou mayst in me behold. Scored for three male lines against a female two to reflect the weighted melancholy of Shakespeare’s text, Little writes more emphatically modally in a deliberate tribute to the Italian madrigal tradition as exemplified specifically by Carlo Gesualdo. There is a semi-aleatory aspect to the central panel, in which singers are given a range of notes to choose from; at this point, too, in live performance one can see the baritones and basses move to the center of the stage while the rest of the choir moves backwards and further out to form an arc. The actual choice of pitches is the composer’s, and ensures a continuity of harmonic language, but the change in choral color is undeniably clear. The performance itself is unbearably gentle, even wistful, with the emphasis on lower registers underlining the sense of regret.

A superb disc, one that simply gets better on each and every listening. There is a radiance to Little’s writing that seems shot through with spiritual light and which speaks on a very deep level to the listener.

Colin Clarke

CONCISE REVIEW SUMMARY

Fanfare (USA)

• ‘The disc of sacred and secular choral and polychoral music by Jonathan David Little, Woefully Arrayed … is nothing short of remarkable. Stunningly recorded, the pure sonic joy is visceral. On a personal level, I haven’t experienced such revelation in choral terms since the Tallis Scholars’ first recording of the Allegri Miserere. … Woefully Arrayed is a masterpiece … radiant … A superb disc … shot through with spiritual light and which speaks on a very deep level to the listener.’ – Colin Clarke, “The Profundity of Polychoralism: Exploring the work of Jonathan David Little” (extended interview), and “Little, Woefully Arrayed …” (CD review), in Fanfare, Vol.41, No.2 (Nov./Dec. 2017) (USA)

Fanfare Contributor Bio

Colin Clarke

Colin Clarke was a manager in the classical department of the record shop at No. 1, Piccadilly, London (Zavvi; ex-Virgin Records). He read music at the University of Surrey (submitting a dissertation on the early world of Alban Berg) before studying Musical Theory and Analysis at King’s College, London with V. Kofi Agawu and Professor Arnold Whittall (completing with a dissertation on “Wagner’s Art of Transition: An Analysis of selected passages from Act II of Wagner’s Parsifal”). He writes and has written for a variety of publications, including Tempo (Cambridge University Press), Fanfare (USA), Classical Recordings Quarterly (CRQ, formerly Classic Record Collector) and International Piano. He has also worked in Classical Music Copyright (Faber Music Limited, MCPS), and on the editorial teams of Gramophone and International Record Review.

"WOEFULLY ARRAYED": Sacred & Secular Choral & Polychoral Works [NEW CD on NAVONA, USA] (2017)

(external link)

!["WOEFULLY ARRAYED": Sacred & Secular Choral & Polychoral Works [NEW CD on NAVONA, USA] (2017)](/ppks/download.aspx?id=sjnu2ymbjXA-.jpg&pr=1)

As a follow-up to his successful 2012 CD "POLYHYMNIA" – featuring three European orchestras – JONATHAN DAVID LITTLE, a former Collard Fellow in Music, has released a new album of choral and "polychoral" works on the US Navona label. Entitled "WOEFULLY ARRAYED", this CD features three choirs from the US and UK, contains diagrams of all the choral forces involved, and an essay on ‘Polychorality’ by Hugh Keyte. It is sponsored by an inaugural Australia Council ‘International Arts Project Award’.

FIRST ADVANCE REVIEW (and IN-DEPTH INTERVIEW), in FANFARE (USA):

"Woefully Arrayed is a masterpiece … A superb disc, one that simply gets better on each and every listening. There is a radiance to Little’s writing that seems shot through with spiritual light and which speaks on a very deep level to the listener. ... On a personal level, I haven’t experienced such revelation in choral terms since the Tallis Scholars’ first recording of the Allegri Miserere."

– Colin Clarke, “Little, Woefully Arrayed …”, in Fanfare (Nov/Dec 2017) (USA)

REVIEW in AUDIOPHILE AUDITION (USA):

"This album is a delight on all fronts. … Little achieves unique and beautiful effects through spacing and arrangement of vocal groups. It seems that Little’s techniques are well grounded in both very careful construction of harmonies and voicing as well as in acoustics and the physics of sound. … In fact, two of the most fantastically beautiful works in this collection—Gloria, op.18 and Wasted and Worn, op. 6, also have atypical and unique placement of the singers. … Of the six selections herein, I would be hard pressed to pick a favorite … When I hear music of this sort it reminds in the best possible ways of when I have actually had the pleasure of hearing music by Tallis or Dunstable in a large old marble clad cathedral … Very enjoyable, highly recommend!"

- Daniel Coombs, “Jonathan David LITTLE: Sacred and Secular Choral & Polychoral Works”, in Audiophile Audition, August 1st, 2017 (USA)

OTHER RECENT ORCHESTRAL AND CHORAL SUCCESSES:

(January, 2017) Composer Jonathan David Little recently received Special Distinction for his orchestral showpiece, "Terpsichore", in America’s 2017 Nissim Prize – one of the concert music world’s most esteemed awards. He was personally congratulated from New York by ASCAP’s Head of Concert Music, Cia Toscanini.

(October, 2016) In 2016, Jonathan was winner of a Royal Philharmonic Society / BBC Radio 3 ‘ENCORE Choral’ Award, and was also invited to participate in a BBC Singers’ Choral Music Workshop, led by Judith Weir.

"Woefully Arrayed": Fanfare magazine - first advance review (2017)

(external link)